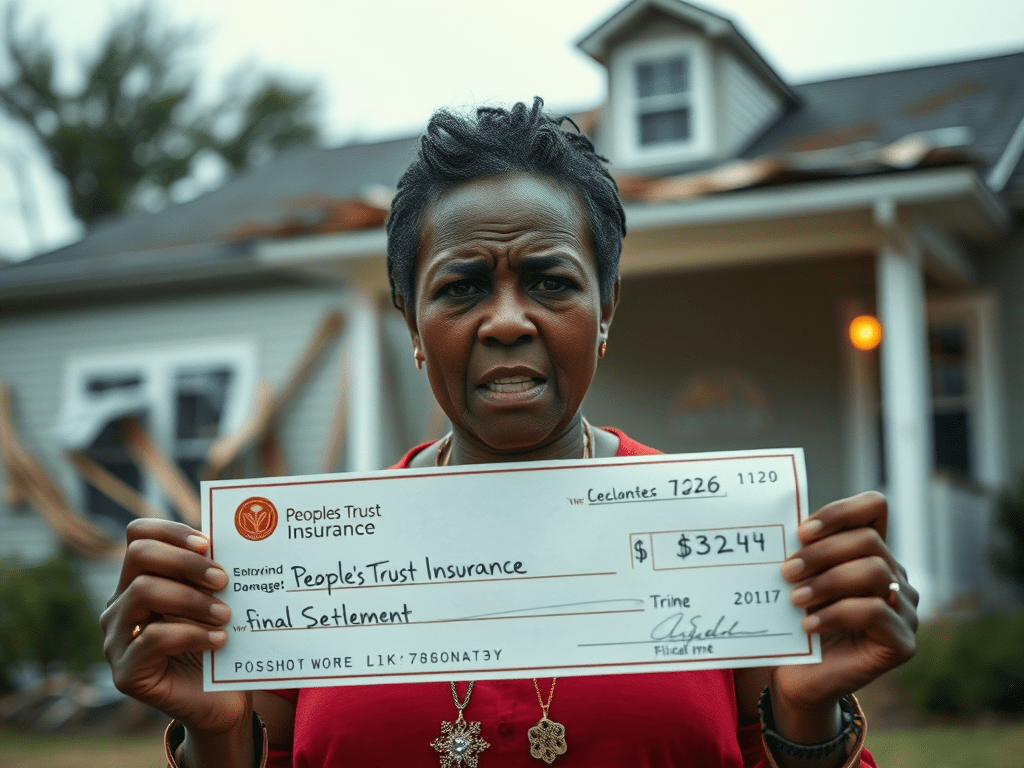

Did your property insurance company send you a check and try to tell you that if you negotiate it, you will be accepting that amount as a final settlement of your claim? (Or, more likely, the insurance company won’t tell you that; they’ll try to sneak it into the “memo” line of the check and then play “gotcha” later.) The insurance company can’t do that. I recently learned that People’s Trust Insurance Company (“PTI”) is still trying to illegally do that, even after it was the losing party in a recent case (decided just last year) that is on point. First, PTI causes confusion by referring to their 100%-wholly-owned-subsidiary “preferred contractor,” and then they try to get you to cash a small check that says “final settlement” on it. What Florida law requires, however, is that insurance companies immediately pay any undisputed damages immediately, without conditioning acceptance of that money on accepting that total as a final settlement of the claim.

In Lemon v. People’s Trust Ins. Co., 344 So. 3d 56 (Fla. 5th DCA 2022), the Fifth District considered an appeal of a final judgment rendered in favor of PTI after a jury trial. The Lemons’ home sustained damage caused by Hurricane Matthew, and after cashing PTI’s check covering the cost to repair the roof, fence, and master bedroom ceiling, the Lemons subsequently discovered additional damage to their home and sought to supplement their damage claim with PTI. PTI refused additional payment because, it asserted, the Lemons’ act of cashing the check constituted full settlement of all claims, and thus their supplemental claim was barred by accord and satisfaction. The jury agreed with PTI, determining that while the Lemons had a supplemental claim against PTI, that claim was barred by accord and satisfaction. On appeal, the Lemons argued that they were not precluded from submitting a supplemental claim because neither common law nor statutory accord and satisfaction applies. The appellate court agreed with the homeowners and reversed the final judgment.

The Lemons’ home was damaged by Hurricane Matthew on October 6, 2016. They reported their damage claim to PTI, and the property was inspected on December 8, 2016. Eleven days later, on December 19, 2016, PTI sent the Lemons two letters. One letter advised the Lemons that there was coverage for the loss and that PTI had elected to use its preferred contractor, Rapid Response Team, LLC (“RRT”) to repair their property. The letter further advised:

Sometimes this scope changes as repairs move forward and new conditions are discovered. If that happens, you have the right to supplement your claim to include newly discovered damages so long as they are damages which are covered under your policy.

The letter instructed the Lemons how to proceed if they did not agree with the scope of repairs attached to the letter, but if there was no disagreement, the assigned adjuster or RRT would be contacting the Lemons to request execution of a written work authorization granting permission for RRT to commence repair work.

The scope of repairs document attached to the letter stated in pertinent part:

Please refer to the enclosed itemized estimate. This estimate contains our scope and valuation of the damages for the reported loss and was prepared using reasonable and customary prices for your geographic region. If any hidden, or additional damage and/or damaged items are discovered, please contact me immediately. Coverage for hidden or additional damages and/or damaged items, would need to be determined, and may require an inspection/re-inspection for further consideration. Please do not destroy, or discard any of the hidden or additional damages and/or damaged items, until we have had an opportunity to review and inspect the hidden or additional damages and/or damaged items.

The other letter sent the same day, titled “Claim Settlement Letter,” contained statements inconsistent with those in the previously described letter. It stated that PTI had been unable to obtain an executed work authorization from the Lemons and, as a consequence, PTI was foregoing its right to repair covered damages using RRT and instead was issuing them a check for $15,286.40. The Claim Settlement Letter falsely stated that there had been an agreement on the amount: “This agreement is based upon our mutual agreement as to the scope and amount of your loss.” It continued:

Your endorsement of this check memorializes your acceptance of the scope and amount of damages we previously reviewed and as reflected in the attached estimate, it is offered solely to bring about a complete and final resolution of your claim. If, for one reason or another, you choose not to endorse the enclosed check, or you no longer agree with scope and/or amount of loss we previously agreed upon, please notify the undersigned at your earliest convenience and PTI will proceed with repairs in accordance with the E023 Preferred Contractor Endorsement, and any scope disputes will be resolved in accordance with the scope dispute mechanism in your policy.

(Emphasis added). As an aside, it is amazing that an insurance company could be that amateurishly boorish–it’s almost cartoonish–in this day and age. It is very well settled–and engrained in the Florida Statutes very clearly–that an insurance company has to pay any undisputed damages payments immediately and cannot condition the receipt of these monies on the homeowner accepting the amount as a final settlement.

On December 20, 2016, the day after PTI sent the letters to the Lemons, PTI issued a check to the Lemons in the amount of $15,286.40, which it reissued on December 28 because the first check was made out to an incorrect mortgagee. The check stub bore the notation: “REASON: FULL AND FINAL PAYMENT — Full & final settlement in accord w/claim settlement.”

Approximately a month after cashing the check, the Lemons discovered more moisture damage in their home’s ceilings, garage, and home office and advised PTI, through a public adjuster, of their supplemental claim. Ultimately, the Lemons submitted a Sworn Proof of Loss claim to PTI for $35,155.53. When PTI did not respond to their claim, the Lemons filed the underlying breach of contract action. PTI answered and raised, pertinent to this appeal, accord and satisfaction as an affirmative defense:

As its First Affirmative Defense, without waiver of any defense as to coverage based the terms and conditions of the policy, Defendant asserts that the Plaintiffs’ claim and lawsuit are barred by Accord and Satisfaction. Plaintiffs and Defendant reached a mutually agreed settlement of Plaintiffs’ entire claim and Defendant issued the mutually agreed payment to Plaintiffs in performance of the settlement agreement.

The affirmative defense made no distinction between common law and statutory accord and satisfaction.

At trial, the Lemons testified that prior to PTI’s issuance of the check, they never had any conversations with PTI that quantified the amount of damage to their home. Rather, PTI unilaterally determined the amount of loss it was going to pay based on an agreed-upon scope of work; the Lemons did not dispute the amount of the check as payment for the unilaterally determined amount of loss because they understood they could file a supplemental claim later if needed. Such supplemental claim was necessary because the Lemons discovered additional damage to their home after depositing PTI’s check.

After the Lemons rested their case, PTI sought a directed verdict, arguing that once it tendered the check and the Lemons accepted it, there was an accord and satisfaction that barred any further recovery. The trial court denied the motion, and PTI presented its witnesses. None of PTI’s witnesses testified to the existence of any dispute with the Lemons prior to the Lemons’ supplemental claim.

After PTI’s final witness, the Lemons moved for a directed verdict on PTI’s accord and satisfaction affirmative defense, arguing that it was undisputed that at the time the Lemons accepted and cashed the check, the parties agreed that the Lemons could submit supplemental claims should they uncover further damage. The Lemons asserted that there was no evidence of a superseding agreement or a mutual intent to settle a dispute, and accordingly, PTI had not met its burden to establish the requisite elements of common law accord and satisfaction. The court denied their motion and submitted the case to the jury. The jury determined that while the Lemons had a supplemental claim for damage discovered after their acceptance of PTI’s check, the supplemental claim was barred by accord and satisfaction. The Lemons filed a Motion for Judgment in Accordance with Prior Motion for Directed Verdict or Motion for New Trial, which the court denied.

On appeal, the Lemons asserted that their supplemental claim could not have been the subject of accord and satisfaction—common law or statutory—as a matter of law because they had the right to submit a supplemental claim for newly discovered damage, and thus they were entitled to a directed verdict and/or judgment notwithstanding the verdict on PTI’s affirmative defense of accord and satisfaction. The appellate court agreed.

The court’s reasoning is noteworthy:

At the time PTI sent the Lemons the check, the only damages of which the Lemons and PTI were aware were to the roof, the fence, and the ceiling of one bedroom. As such, those were the only damages adjusted by PTI at that time. Indeed, the scope of repairs document, Claim Settlement Letter, check, and check stub referenced neither the ceiling spots nor the water damage to the home office, which were the subject of the supplemental claim. PTI’s check stub bore the notation: “REASON: FULL AND FINAL PAYMENT — Full & final settlement in accord w/claim settlement” — which requires reference to the letter titled “Claim Settlement Letter” that further described the purpose of the check. The Claim Settlement Letter advised the Lemons that PTI was issuing a check for $15,286.40 and that if they endorsed the check, the endorsed check “memorializes your acceptance of the scope and amount of damages we previously reviewed and as reflected in the attached estimate.” (Emphasis added). The “scope and amount of damages we previously reviewed” was indisputably a reference to the roof, fence, and ceiling claim because no other damages had been submitted, claimed, or reviewed at that time. Thus, the “final resolution of the claim” was the final resolution of the claim for damages being adjusted at that time.

The court held that PTI’s performance in delivering the check to the Lemons was no more than what it was contractually obligated to do, having chosen to pay rather than repair, and there being no challenge to the amount it tendered. In other words:

PTI’s payment of $15,286.40 was not a substitute for a previously agreed amount or performance.” Rather, it was the performance expected by the Lemons in the first place. Because under no view could the language on the check evince an intention to settle future, unknown supplemental claims, the motion for directed verdict on the accord and satisfaction defense should have been granted as a matter of law. See Luciano v. United Prop. & Cas. Ins. Co., 156 So. 3d 1108, 1110 (Fla. 4th DCA 2015) (holding, where insurer’s 2006 letter indicated check was net settlement only for skylight replacement, and no check or letter indicated payment in full for, or a complete settlement of, all Hurricane Wilma claims or indicated that no additional supplemental payments would be made, checks “merely evidence performance under the insurance policy and United’s alleged breach did not occur until United denied the claim for roof replacement in 2010”); Rizo v. State Farm Fla. Ins. Co., 133 So. 3d 1114, 1115 (Fla. 3d DCA 2014) (observing that prior checks tendered by insurer to cover hurricane damages were not marked “in full and final payment” nor did they “anticipatorily preclude the possibility of supplemental claims or payments”); see also Roll v. Spero, 293 So. 2d 370 (Fla. 4th DCA 1974)(holding plaintiffs not precluded from recovering further amounts under contract where they had cashed a check containing the phrase “Paid in Full to date of abeyance” where invoice related to check showed check was a progress payment and no dispute existed between parties at time check was cashed).

The court further explained its rationale for finding in favor of the homeowners:

Because the language of the check tendered in satisfaction of the original damage claim is susceptible of only one interpretation—that it was offered (and accepted) in settlement of only the damages claimed and adjusted as of that date—and there was no evidence whatsoever of the parties’ intent to preclude supplemental claims, it was error to deny the Lemons’ motion for directed verdict and subsequent motion for judgment notwithstanding the verdict on PTI’s affirmative defense of accord and satisfaction. Accordingly, we reverse the Final Judgment and remand for further proceedings consistent with this opinion.

Even though this decision making People’s Trust the loser was issued last year, and the law is very clear, I have a client who is experiencing People’s Trust attempting to make the exact same (rejected by the courts) argument right now. Looks like we will be filing a lawsuit soon.

*** Tangentially related bonus point for existing clients and potential clients who might want to challenge an insurance company’s actions: you have to be willing and able to be patient. As the court in Lemon noted, Hurricane Matthew hit central Florida on October 6, 2016. People’s Trust did what it did, and the Lemons finally received their victory in the appellate court nearly six years after the date of loss, on June 3, 2022 (not final until rehearing was denied August 2, 2022). Simply put, that’s our overburdened judicial system. The wheels of justice move slowly. Even if you’re right and you are going to win, it could take six years for the court system to provide the result that you are the winner. That is why insurance companies don’t just make large settlement offers in response to demand letters or even the filing of a lawsuit. They know they can make you wait. Nowadays the average trial in a first-party property insurance case occurs about three years after the lawsuit was filed. P.S. Even the Lemons’ victory is not a total victory; all they won was the right to another jury trial to determine their damages. The appellate court reversed the entry of judgment for the insurance company, but a new trial (in the absence of a settlement) was needed to determine the Lemons’ damages. I am not involved in their case, but I note that at the time of publishing this article, it appears that the case has not been settled and the Lemons have not yet received their second trial. ***