Florida family courts operate in difficult terrain. Judges are asked to manage high-conflict relationships, protect children, and reduce the emotional and physical fallout of failed marriages. Those pressures often intensify when a new spouse or partner enters the picture and becomes part of the conflict.

Miller v. Velleff, decided by Florida’s Fourth District Court of Appeal in January 2026, is an important reminder that even in that context, trial courts remain bound by fundamental limits: due process, jurisdiction, and the distinction between parenting authority over parents and injunctive power over third parties.

The case is not about whether courts should act when conduct becomes aggressive or disruptive. It is about how courts must act — and who they may lawfully bind — when doing so.

THE FACTUAL BACKDROP

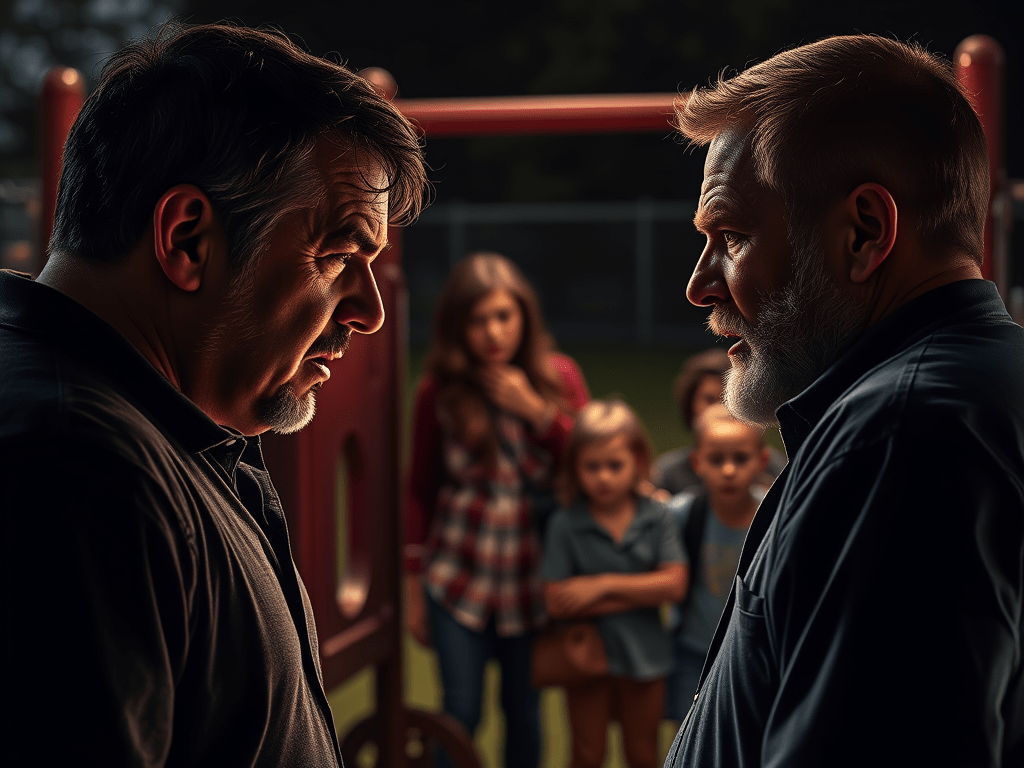

The parties divorced in 2016 and share one child. Several years later, the former husband sought modification of child-related provisions, alleging that the former wife’s current husband had engaged in hostile, aggressive, and allegedly violent conduct toward him at child-related events and during exchanges.

The former husband testified to a physical confrontation at a school graduation, hostile verbal encounters, and audio recordings he believed demonstrated threatening behavior. A temporary injunction had previously been entered following the graduation incident, but no permanent injunction was ever obtained.

After an evidentiary hearing, the trial court entered a supplemental final judgment. Among other rulings, the court prohibited the former wife’s current husband from attending the child’s public school, extracurricular, and religious events if the former husband provided advance notice that he intended to attend. The order also barred the current husband from attending timesharing exchanges and certain appointments.

The current husband, however, was not a party to the modification proceedings. He was never joined, never served, and never afforded an opportunity to be heard.

The former wife appealed.

WHAT THE FOURTH DISTRICT AFFIRMED — AND WHAT IT REVERSED

The Fourth District affirmed most of the trial court’s rulings without discussion, including the denial of modifications to child support and timesharing and the award of makeup time.

But it reversed the portion of the order restricting the current husband from attending the child’s public events.

That distinction is critical. The appellate court did not disturb the trial court’s factual findings regarding conflict or hostility. Nor did it suggest the trial court lacked authority to manage parenting issues between the parties themselves. The reversal turned instead on legal limits — not factual disagreement.

DUE PROCESS STILL APPLIES IN FAMILY COURT

The first ground for reversal was procedural due process.

A court may not impose restrictions on an individual without providing notice and a meaningful opportunity to be heard. That principle applies regardless of whether the proceeding is civil, family, or equitable in nature.

Because the current husband was not a party to the case and received no notice, the restriction violated his due process rights. The appellate court emphasized that even well-intentioned efforts to protect a child cannot dispense with basic procedural protections.

This aspect of the decision aligns with long-standing Florida authority, including cases such as Trans Health Management, Inc. v. Nunziata and Spencer v. Kelner, which reinforce that due process is not optional simply because a court believes the outcome is justified.

THE ORDER FUNCTIONED AS AN INJUNCTION — AND THAT MATTERS

The Fourth District also focused on the nature of the relief itself. Although framed as a parenting-plan modification, the restriction operated as an injunction against the current husband.

Florida law is clear: an injunction cannot bind non-parties.

Cases such as Leighton v. First Universal Lending, LLC, Trisotto v. Trisotto, Silvers v. Silvers, and Hastings v. Rigsbee all stand for the same basic proposition — a court lacks jurisdiction to issue injunctive relief that interferes with the rights of individuals who are not before it.

Embedding an injunctive restriction inside a family court order does not change its character. Substance controls over form.

WHY WILCOXON v. MOLLER DID NOT SAVE THE ORDER

The trial court relied on Wilcoxon v. Moller, which included a provision restricting a former spouse’s current husband from being present at events where the former husband was in attendance.

The Fourth District explained why that reliance was misplaced. In Wilcoxon, the propriety of the restriction was not actually litigated on appeal. The opinion did not analyze jurisdiction, due process, or injunctive authority over non-parties. As the trial court itself acknowledged, the issue was never directly addressed.

That matters because unexamined language in prior orders does not create binding precedent on questions that were never decided.

NO “BACKDOOR” INJUNCTIONS THROUGH MODIFICATION PROCEEDINGS

One of the most practically important aspects of Miller is the court’s explicit rejection of procedural end-runs.

The former husband had previously sought a permanent injunction against the current husband and failed to obtain one. The Fourth District made clear that modification proceedings cannot be used as an alternate or “backdoor” method of achieving permanent injunctive relief against a non-party.

That observation reflects a broader concern: if courts could restrain third parties through parenting orders without notice or service, Florida’s injunction procedures — and the protections they provide — would become meaningless.

WHAT THE DECISION DOES NOT HOLD

Miller v. Velleff is not a decision that strips trial courts of authority to manage dangerous or disruptive behavior. It does not suggest that courts must ignore stepparent conduct or tolerate hostility in front of children.

It also does not decide whether a trial court may impose conditions on a parent — who is a party — that indirectly limit the involvement of a non-party spouse. The Fourth District expressly declined to address that question, leaving it for another case.

The holding is narrower but more fundamental: a court may not directly restrain a non-party’s conduct at public events without jurisdiction, notice, and due process.

PRACTICAL IMPLICATIONS

For parents, Miller underscores that family court authority, while broad, is not unlimited. Orders that directly restrict third parties require proper procedure.

For lawyers, the case is a reminder to align remedies with process. Parenting-plan modification is not a substitute for injunctive relief. If the relief sought walks, talks, and operates like an injunction, it must be pursued as one.

BOTTOM LINE

Miller v. Velleff is a reaffirmation of first principles. Even in family court — perhaps especially in family court — courts must respect jurisdictional limits and procedural fairness.

Protecting children and preserving due process are not competing values. Florida law requires both.